Rabble, Revolution, Representation

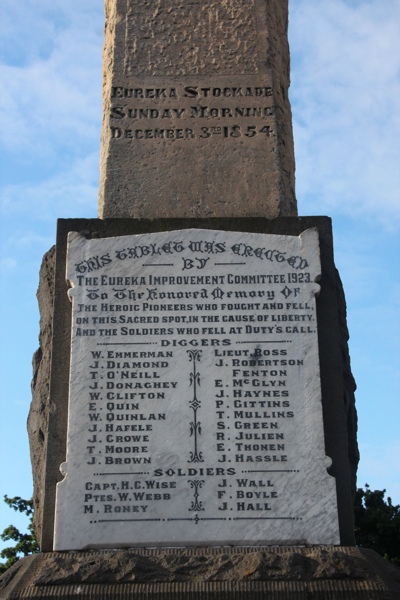

Early on 3 December 1854 British military forces and police stormed a stockade built by protesting miners at Eureka on the Ballarat goldfields, leaving about thirty diggers and troops dead.

Ever since, various cultural and artistic depictions of the Eureka Stockade have attempted to portray the event in a way consistent with a particular ideology or cause. On the first anniversary of the Stockade, Rafaello Carboni, who had been present and wrote a firsthand account, read the famous Eureka proclamation on Bakery Hill where the battle had occurred to commemorate the dead.

The use of the ‘Eureka legend’ has become a common theme in Australian political discourse over the years, with both left-wing and right-wing causes evoking the spirit of the Eureka Stockade to give their cause historical and national meaning.

American Mark Twain wrote:

Contemporary accounts of the battle focused on a matter-of-fact telling of the events, although accounts like Carboni’s naturally put a particular spin on things. A generation later, in the late 19th-century, Eureka began to turn from an historical event into a legend, viewed with awe and reverence, especially in Victoria. Enough time had passed for people to reflect on the meaning of the Eureka Stockade and its implications. The meaning given to Eureka around this time was overwhelmingly positive and romantic.

The image above—a print by Beryl Ireland from the 1890s—illustrates the battle graphically, portraying it as a violent massacre. Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

The Ballarat miners protested, petitioned and complained—it was of no use; the Government held its ground, and went on collecting the tax. And not by pleasant methods… By and by there was a result; and I think it may be called the finest thing in Australian history. It was a revolution—small in size, but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for a principle, a stand against injustice and oppression… It is another instance of a victory won by a lost battle. It adds an honourable page to history; the people know it and are proud of it. They keep green the memory of the men who fell at the Eureka Stockade.

Another influential figure who wrote about Eureka in gloried terms was Karl Marx, author of the Communist Manifesto. In an 1855 article in the newspaper Neue Oder-Zeitung, Marx reported:

We must distinguish between the riot in Ballarat (near Melbourne) and the general revolutionary movement in the colony of Victoria. The former will have been suppressed by now; the latter can only be suppressed through complete concessions. The former is by itself only a symptom, an incidental eruption of the later… The really important questions at issue, around which the revolutionary movement in the province of Victoria revolves, are two. The gold diggers demand abolition of the licences for gold prospecting, ie, a direct tax on labour; secondly they demand the abolition of the property qualification for members of the Chamber of Representatives… It is not difficult to notice that these are essentially similar reasons to those which led to the Declaration of Independence of the United States, but with the difference that in Australia the opposition arises from the workers against monopolists tied up with the colonial bureaucracy.